|

| Forest in Autumn, 1841 by Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) |

There are many wonderful books in the world. There are even more lousy ones and the number of books that are just mediocre would astound you. Even with the best of intentions, boundless curiosity and a life free from toil and obligation, one can never hope to read but a fraction of all the books you hope to read. When I was a bright-eyed youth studying English lit, I thought my professors had read everything, but now I know it’s very likely that they hadn’t. At least it seemed a statistical improbability given the sheer number of works of literature versus the number of hours in a day. But you can relax. You don’t have to read absolutely everything in order to enjoy literature.

Look at this syllabus from a class taught by poet W. H. Auden in 1941. It is ridiculous—six thousand pages of reading for one class in the span of a single semester. It is a workload that sets the bar impossibly high. This kind of binging could potentially lead to serious mental health problems and feelings of intellectual inadequacy. But remember, one could spend a lifetime climbing that mountain of classics and still only scratch the surface of Western civilization. And that’s not counting time for reflection and meaningful analysis. I never received a syllabus quite like this one, but I have seen a few daunting ones in my time. It took me years not to be intimidated by other people’s expectations of what I was supposed to have read. I eventually learned to enjoy my journey through literature and history in my own way at my own pace—in essence, drafting my own syllabus. I often consult those with knowledge of literary criticism and the art of writing and their insight is often helpful, but I’m not beholden to anyone’s expectations but my own. That’s what The Overleaf is all about—crafting your own course of discovery.

So far, I’ve kept to a self-imposed schedule of two blog entries per month. I’ve done that for a solid year and built up the blog, giving it a firm foundation. Time is now increasingly short and obligations demand more of my time, so I’m cutting back to monthly posts. But the literary journey continues. Rather than keep to the stringent demands of a bi-monthly binge and purge cycle, cutting back will allow me to spend more quality time with the books I share with you and still have time to work and buy food. This new arrangement is the epitome of a win-win.

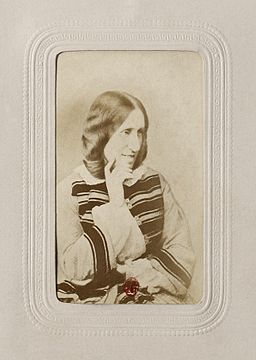

Here is a book that may not be on your syllabus yet unless you’re enrolled in a class about rarely read nineteenth century French novels. The Devil’s Pool depicts rural French peasant life. It’s author, George Sand was actually a woman (Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin), a renowned writer of novels and committed socialist whose unconventional lifestyle and numerous romantic flings with prominent writers and composers like Alfred de Musset and Frederic Chopin made her a bit of a celebrity. She was widely read throughout Europe and America and had vocal supporters from literary giants of her day like Walt Whitman and Ivan Turgenev. This novel is short and straightforward and provides a broader context to some of the stories we’ve read earlier this year about the Russian peasantry. The fact that she isn’t read as much these days is reason enough to give The Devil’s Pool a spin.

|

| "The Ploughman" c. 1525 by Hans Holbein the Younger (1498-1543) |

This story was inspired by Dance of Death, a book of wood cut prints by Renaissance artist and printmaker Hans Holbein. One print in particular, “The Ploughman” (right) shows Death running along side an emaciated farmer and his team of oxen. George Sand was struck by how this grim depiction of peasant life in which the inevitability of hardship and toil are rewarded only by the promise of the reward of death contrasted sharply with the reality of peasant life as she witnessed it near her home in the French countryside. While out for a walk, she saw a healthy young man driving a team of newly yoked oxen goaded not by the spectre of Death, but by the farmer’s young son. She mused that perhaps depictions of peasants centuries ago overemphasized the omnipresence of suffering and barbarity. She saw that her peasant neighbors had a deeper, often more joyful connection to the natural world that eluded those who lived removed from nature. She set out to write a book that would right this wrong.

The tale she tells is a simple one. Germain is a widower with three children who lives with his in-laws, helping to run the family farm. He is twenty eight years old—an old man by peasant standards, but exceedingly strong and good looking. His father-in-law suggests to him that perhaps it’s time that he found a wife to help take care of his children—preferably one with a bit of money and property to help the family. Still mourning the death of his wife, Germain nevertheless concedes to travel to meet with a prospective match his father-in-law has in mind. Before setting out on his journey, Germain learns that his neighbor Marie, a virtuous, kind and beautiful sixteen year old shepherdess has secured as a position at a farm near to where Germain is headed and needs a ride to her new digs. You can probably already guess where this is leading.

Along the way, they spot Germain’s little boy, Petit Pierre, who insists on coming along. He joins them on the back of their grey mare and heads into the forest in the loving arms of Marie. Along the way, they become lost in the mists of the forest as night falls, settling along a small pond, revealed later to be the Devil’s pool—a place where it is believed that passers-by are bewitched into a state of confusion and fear. Marie proves herself to be resourceful, wise and a loving companion to Pierre, and Germain starts to fall in love with her, although she insists that he is too old for her and that she does not love him. Love sick but resigned to his fate, the next morning, Germain arranges for Marie to take care of his boy as he presents himself as a suitor to his perspective bride.

|

| George Sand (1804-1876) |

I have a no spoiler policy when describing books, but the plot of this novel is so simple and predictable that it’s not a stretch to assume that you’ve already figured out that these two get together. The devil’s pool, believed to inspire fear and confusion, seems to have brought Germain and Marie to a moment of clarity. But plot is not the main attraction here. Rather, it’s how Sand depicts these rural characters as simple, virtuous people who experience life unfettered by vanity and artifice and who have close ties with nature and who embrace their ancient Gallic customs and traditions. The complicated rites and ceremonies of the wedding celebration are described in great detail, as is a fertility rite that takes place after the wedding.

Sand’s portrayal of France’s peasantry stands in contrast with similarly themed stories and novels by her Russian counterparts. Although her style is unmistakably realist, she has buffed the images of her characters to a glossy, sparkling, idealized spit shine to reveal an image that middle class readers could easily relate to. Sand’s peasants respond to the hardship of their lives with unyielding stoicism and are upright, moral, sensible and respectable—all attributes held dear by middle class readers. They struggle with hunger and labor for their livelihood, but there is none of the constant drunkenness, squalor and wretchedness found in Dostoyevsky’s peasants, nor is there a trace of the oppressive, inhumane treatment by landowners found in Turgenev. In fact, Russian peasants in the 1840s would be envious of their French cousins, who seem to be having an absolute blast by comparison. The Russian authors we’ve encountered depicted the realities of peasant life unflinchingly, not by portraying them as stoics with a sense of propriety that mirrored the world view of their readers, but as human beings with virtues and flaws who suffered at the mercy of a social and economic system run by allegedly “decent” people whose cruelty and deprivation robbed those in their charge of their very humanity. Nineteenth century rural France was certainly a world away from feudal Russia, but things seem a little too tidy in Sand’s world all the same.

But yet, this novel has its charms. Sand’s is a compassionate voice. She really wants us to understand and identify with her characters and to see them in context with the natural world. She has a great feel and affinity for nature. Her imagination was stirred by the ancient Gallic marriage rites and rituals at a time when these traditions were dying out as industrialism spread, so on one level the novel serves as a little slice of fictionalized cultural anthropology. We see them not through a veil of tears, but through a halo of morning sunlight that shines down on a people closely linked with the traditions of their ancestors and on a way of life rapidly fading away. This novel is a snapshot, albeit airbrushed, of that time, but was written with the very best of intentions. It’s a pleasant read with some merit. In the pantheon of wonderful, lousy or mediocre books, The Devil’s Pool can easily be classified as “good”.

Download The Devil's Pool from Project Gutenberg.

If you enjoy reading eBooks prepared by Project Gutenberg, I urge you to make a donation to this non-profit, mostly volunteer organization. They're giving books back to the world absolutely free and giving a little money back will help them continue to do so.

Download The Devil's Pool from Project Gutenberg.

If you enjoy reading eBooks prepared by Project Gutenberg, I urge you to make a donation to this non-profit, mostly volunteer organization. They're giving books back to the world absolutely free and giving a little money back will help them continue to do so.

.jpg)

_-_Geographicus_-_USAwall-mitchell-1844.jpg)