Premonition By Henryk Weyssenhoff (1859-1922) Oil on canvas, c. 1893

In this post, we'll take a look at two pieces of short fiction--call them novellas or novelettes or whatever you like--by two very different English writers: Edward Bulwer-Lytton and George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans). Both stories were published in 1859 and both deal with the supernatural, which is unsurprising given the popular Victorian obsession with the occult, mesmerism and psychic phenomena. One story is a prototypical ghost story with a hefty dose of esoteric theorizing, the other a hybrid that combines elements of science fiction in the gothic tradition and a narrative technique that was ahead of its time. The first story aspires to rationality and objectivity, the other is told through a gauzy mesh of subjectivity.

Edward Bulwer-Lytton was a prolific writer of novels, mostly historical fiction, along with some verse and a few plays that span a career of over six decades (we looked at two of his books last year). His prose could be a bit flabby and pompous, but he was an internationally known literary rock star, and while his work falls short of what many consider truly timeless, classic literature, a few of his novels are at least fun to read. George Eliot was one of the greatest English novelists who ever lived and whose work set new standards for the novel as an art form in the mid-nineteenth century. Bulwer-Lytton was an aristocrat and politician who was very interested in unexplained phenomena and theosophy; Eliot was an intellectual heavyweight and dyed-in-the-wool rationalist of more humble means who shared similar interests. When these stories were first published, he was close to the end of his long career and she was just beginning hers. Today, her books continue to be read and studied, his not so much.

In addition to being fine Halloween reading, taken together, these two pieces display an interesting contrast of narrative styles.

|

| Edward Bulwer-Lytton 1803-1873 Illustration by Carlo Pellegrini |

This first person narrative is a matter-of-fact account of a night spent in a haunted house on Oxford Street in London. Upon hearing a friend's account of an abortive attempt to rent and occupy rooms there for a week (they lasted three days), the narrator, excited by the idea of spending a night in a haunted house soon comes to agreeable terms with the owner and sets off with his manservant, his dog, a revolver and a dagger. For the narrator, this is a fact-finding mission to observe and find rational explanations for so-called supernatural phenomena, and he relates what happened in great detail.

Things start off with the usual hearing of footsteps, the moving about of furniture, mysterious letters and a cold, depressing room that functions as the "heart" of the house. As night approaches, a dark, weighty, will-quenching oppression grips the heart of the narrator as ghosts from the house's past play out the circumstances that led to their tragic ends. These gothic, melodramatic elements are kept in check by the narrator's persistence of will to remain objective by resisting fear. Indeed, that's a central theme of the story; by not succumbing to fear, a rational explanation for seemingly otherworldly phenomena can be found in the form of a human agency rather than a supernatural one.

I won't spoil the story for you, but the convoluted explanations found for these disturbances are obscure, to say the least. While the author's journalistic style strives for objectivity, the pseudo-scientific blather that attempts to explain the disturbances is only so much malarkey. But if one is willing and able to suspend disbelief, The Haunted and the Haunters is a fun ride and a classic ghost tale for the nineteenth century thinking man. Whether you're a true believer or scoffing skeptic, if you have any pulse at all, the ghostly descriptions alone will raise at least a few empirically challenged hairs and inspire purely subjective feelings of dread. This piece can be taken at face value, and that's precisely what we should expect from a good ghost story.

I won't spoil the story for you, but the convoluted explanations found for these disturbances are obscure, to say the least. While the author's journalistic style strives for objectivity, the pseudo-scientific blather that attempts to explain the disturbances is only so much malarkey. But if one is willing and able to suspend disbelief, The Haunted and the Haunters is a fun ride and a classic ghost tale for the nineteenth century thinking man. Whether you're a true believer or scoffing skeptic, if you have any pulse at all, the ghostly descriptions alone will raise at least a few empirically challenged hairs and inspire purely subjective feelings of dread. This piece can be taken at face value, and that's precisely what we should expect from a good ghost story.

|

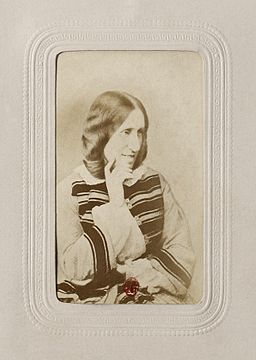

| George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) 1819-1880 |

The Lifted Veil (1859) by George Eliot

This one is something altogether different. In The Haunted and the Haunters, Bulwer-Lytton strives for objectivity, and although the holes in his narrator's logic are large enough for a ghost to fall through, the tone of the story remains one of dispassionate inquiry. In George Eliot's The Lifted Veil, the narrator's point of view is subjective to the point of being untrustworthy, and his morbid fascination with his own psyche colors his interactions with everyone around him.

At this point some of you might want to read the story first before reading my little analysis. I don't exactly spoil the ending, but I do discuss some key story details.

Here is a laughably simplified plot synopsis: Latimer is a sensitive male type in the Romantic tradition, not unlike Goethe's Werther. He prefers nature and poetry to science and business. After a childhood illness, he is seized by intermittent visions of the future and develops the ability to read the minds of those around him. He becomes enamored with Bertha, his brother's fiancee and the only one in his circle whose thoughts he cannot read. Despite glimpses into an grim future in which they are unhappily married, he marries her anyway after his brother is killed in a hunting accident. Their marriage is a disaster, and as time goes on, they drift apart and Bertha becomes inexplicably close and secretive with one of their maids. Dr. Meunier, one of Latimer's school chums, shows up for a visit just as the maid becomes ill with peritonitis. The doctor suggests to Latimer that, since the maid will surely die anyway, he would like to perform an experimental procedure to resuscitate her--namely, to give her a blood transfusion. He does so, and the maid wakes up and speaks of the secret she would have otherwise taken to her grave…but I digress. No spoilers here.

Does Latimer really have psychic powers or has he merely convinced himself of it? He gets a few predictions right, but he ignores the most important one that foretells an unhappy marriage to a cold hearted woman who is incapable of loving him. Even if he had psychic powers, they don't seem to have done him any good. Or is he so self involved that he projects his insecurities and miseries on everyone around him? Why should we believe his tortured version of what happened? Who knows? Who cares?

George Eliot uses a literary device called the unreliable narrator. We should question Latimer's truthfulness because he lacks objectivity. For all we know, the whole story could be a smoke screen. The best parts about using this narrative device is that she can fiddle with how she presents the chronology of events (the story opens with Latimer's death) and keep the attentive reader guessing as to the sanity of her protagonist (although a face value interpretation is also possible). George Eliot made her reputation on realist prose, so this story is a real curiosity and an ambitious experiment in narrative technique that anticipates some of the innovations of modernism by forty or fifty years.

Apart from the clairvoyance, the real sci-fi element of the story doesn't occur until the very last pages. In 1859, blood transfusions were still in the experimental phase and were not known to bring the dead back to life. But hey, we can't blame George Eliot for being a woman of her time, especially when her writing technique and imagination were so far ahead of her time. Although the plot contrivances don't really work, Eliot's prose is as rich and full of the wonderful subtlety and complexity that characterizes her work.

Download The Lifted Veil from Project Gutenberg

As always, if you enjoy reading eBooks prepared by Project Gutenberg, please make a small donation so they can continue to publish free digital editions of vintage books in the public domain.

As always, if you enjoy reading eBooks prepared by Project Gutenberg, please make a small donation so they can continue to publish free digital editions of vintage books in the public domain.